Vision, Mission, Values, and Goals

Vision:

The Meadows Museum’s vision is to be the leading center in the United States for exhibition, research and education in the arts and culture of Spain.

Mission:

The Meadows Museum, a division of the Meadows School of the Arts at Southern Methodist University (SMU), advances knowledge, understanding and appreciation of the arts and culture of Spain through the collection and interpretation of works of the greatest aesthetic and historical importance.

Values:

• Excellence in education, scholarship, and artistic expression

• Aesthetic and cultural traditions that inspire learning, leadership, and creativity

• A welcoming and inclusive spirit

Goals:

• Preserve, study, care for and grow the museum’s collection of Spanish art through responsible stewardship

• Further scholarship of Spanish art history through exhibition, research, education, publication and other academic initiatives

• Expand our role as an integral part of the community and the SMU student experience

• Continue to cultivate local, national and international partnerships that will enrich the experience of our audiences

• Oversee and manage SMU’s University Art Collection

Building on the Boulevard: Celebrating 20 Years of the Meadows’s New Home is a tribute to the achievements made possible by the vital structure. Directed by Quin Mathews.

History

During business trips to Spain in the 1950s, Texas philanthropist and oil financier Algur H. Meadows spent many hours at the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid. The Prado’s spectacular collection of Spanish masterpieces inspired Meadows to begin his own collection of Spanish art. In 1962, through The Meadows Foundation, he gave Southern Methodist University funds for the construction and endowment of a museum to house his Spanish collection. The Meadows Museum opened in 1965 as part of the new Owen Arts Center at SMU. In the years that followed, Algur Meadows provided the impetus and funds for an aggressive, but highly selective, acquisitions program through which an extraordinary collection was developed in a remarkably short period of time. Since his death in 1978, The Meadows Foundation and numerous donors have provided ongoing support for continued development of the museum’s permanent collection, nearly doubling its collection of paintings. The Foundation gave a gift of $18.5 million in 1998 for construction of a new museum building on campus to showcase the collection and provide more space for special exhibitions and educational programs; the new building opened in March 2001. In 2006, the Foundation gave $33 million to the Meadows School of the Arts, the largest grant ever made by the Foundation and the largest ever received by SMU at the time, which included $25 million for the museum for acquisitions, exhibitions, an educational curator position, an expanded educational program, and special initiatives of the museum director. The Museum celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2015, during which The Meadows Foundation made yet another historic gift to SMU of $45 million, $25 million of which was designated to support goals and programs at the Museum.

History Timeline

1950s

General American Oil Company begins searching for oil in Spain in the early 1950s. The venture is commercially unsuccessful, but it affords Meadows the opportunity to spend extended periods of time there. Meadows begins building his collection with the help of Jerónimo Seisdedos, a retired employee of the Prado Museum. After Seisdedos’s death in 1958, Meadows turns to José López Jiménez, a painter, scholar, and art critic who worked under the pseudonym Bernardino de Pantorba. Pantorba advises Meadows well into the 1960s, recommending the purchase of more than sixty paintings.

1961

Meadows’s wife, the former Virginia Stuart Garrison, dies one day before their 39th anniversary; Meadows announces he will donate their art collection to Southern Methodist University.

1962

Through The Meadows Foundation, Algur H. Meadows donates funds to SMU for the construction and endowment of a museum to hold his growing collection of Spanish Art. Meadows meets and marries Elizabeth Boggs Bartholow. An artist herself, Elizabeth prefers modern works to those of the old masters, and encourages Meadows to expand his collection to include sculpture and French art, which he does with the help of the eccentric millionaire and art dealer Fernand Legros and his partner, Real Lessard.

1965

April 3 – Dedication and opening of the Meadows Museum in the Owen Arts Center Building at SMU (pictured, far left).

1967

• Early 1967 – Art Dealers Association of America vice president writes to Mr. Meadows and informs him that many works in his collection are misattributed: The authenticity of several works in the Museum is questioned. Algur H. Meadows determines that the new Museum should contain works of the finest possible quality and a search begins for a curator to remove and replace the questioned pieces.

• Dr. William B. Jordan (pictured, left) joins Museum as director and a new phase of collecting begins and continues until Algur Meadows’s death in 1978, during which the core of the present collection was formed.

• Dr. William B. Jordan (pictured, left) joins Museum as director and a new phase of collecting begins and continues until Algur Meadows’s death in 1978, during which the core of the present collection was formed.

• The Museum acquires Goya’s Yard with Madmen. This painting had not been seen by the public since 1922.

• Acquisition of Velázquez’s Portrait of King Philip IV (pictured, left).

• Acquisition of Velázquez’s Portrait of King Philip IV (pictured, left).

1968

Meadows is quoted in the Houston Chronicle as saying, “I mean…to build a small Prado in Texas,” and the Museum is nicknamed “Prairie Prado” by TIME magazine.

1969

• Clifford Irving writes Fake! The Story of Elmyr De Hory, the Greatest Art Forger of Our Time, featuring the story of Algur H. Meadows (pictured, left).

• May – Algur H. Meadows gives $10 million to SMU’s School of the Arts and the school was renamed Meadows School of the Arts.

• The Museum deaccessions a notable portion of the original misattributed collection.

• Algur H. Meadows makes another major donation of works of art to the Meadows Museum, this time in the form of a collection of modern sculptures by European and American artists. Included in the collection are works by Alberto Giacometti, Auguste Rodin, Henry Moore, David Smith, and Aristide Maillol.

• The Museum acquires Picasso’s Still Life in a Landscape, (pictured, left).

• The Museum acquires Picasso’s Still Life in a Landscape, (pictured, left).

1970

The Museum commissions an important sculpture, Geometric Mouse, by Claes Oldenburg, (pictured, left).

The Museum commissions an important sculpture, Geometric Mouse, by Claes Oldenburg, (pictured, left).

1974

Meadows Museum acquires second Velázquez painting, Female Figure (Sibyl with Tabula Rasa). The eloquent figure is among the most enigmatic of Velázquez’s canvases, representing the artist at the height of his power.

1977

• Meadows Museum hires its first Curator of Education, Nancy Berry, who establishes the first docent program, run by both SMU students and volunteers, along with an array of educational programs for the SMU and Dallas community.

• Acquisition of Ribera’s Portrait of the Knight of Santiago.

1978

• February – Meadows exhibits Andy Warhol’s Portraits (pictured, far left and middle).

• February – Meadows exhibits Andy Warhol’s Portraits (pictured, far left and middle).

• Meadows Museum acquires third Velázquez painting, Portrait of Queen Mariana.

• June 10 – Algur H. Meadows, (pictured, left), is killed in an auto accident; he dies before his final Velázquez arrives at the Museum.

• November 1 – December 3, 1978 Homage to Algur H. Meadows (1899-1978): Contemporary Paintings on view in honor of the late founder.

1979

Isamu Noguchi’s sculpture Spirit’s Flight, (pictured, left), is commissioned by the Meadows School of the Arts to symbolize the Algur H. Meadows Award for Excellence in the Arts.

1985

March – Meadows Museum opens Luis Meléndez: Spanish Still-Life Painter of the Eighteenth Century.

1986

The Meadows Museum is renovated for the addition of special exhibition galleries.

1998

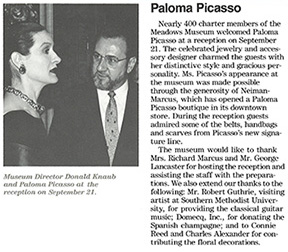

• September 21, 1988 Paloma Picasso (pictured, left) exhibits at the Meadows Museum and showcases her handbags.

• September 21, 1988 Paloma Picasso (pictured, left) exhibits at the Meadows Museum and showcases her handbags.

• Grand Noir, one of the most important works by modern Spanish master Antoni Tàpies, is acquired.

1991

May – Exhibition Ignacio Zuloaga, 1870-1945 opens.

1994

A major work by Juan Bautista Maíno, The Adoration of the Shepherds, is acquired.

1997

1997

May – The Meadows Foundation gives $1.5 million (left) for the architectural design of a new museum building, intended to significantly expand facilities for research, exhibition and educational programming. Chicago-based architectural firm Hammond Beeby Rupert Ainge is selected.

1998

• April 2 – The Meadows Foundation gives $18.5 million for construction of new building and for the establishment of endowments for ongoing building maintenance and expanded educational programming.

• December 3 – Groundbreaking of new Meadows Museum building, (pictured, left).

• December 3 – Groundbreaking of new Meadows Museum building, (pictured, left).

1999

• Acquisition of the only El Greco in the collection (St. Francis Kneeling in Meditation, 1605-1616).

2000

• March 7 – Topping-out ceremony for the new Meadows Museum, (pictured far left).

• March 7 – Topping-out ceremony for the new Meadows Museum, (pictured far left).

• May – Highlights of the collection travel to Spain, (pictured, left), and are on display at the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza (Madrid), followed by the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya (Barcelona).

2001

March 25 – Dedication of the new Museum building by H.R.H. King Juan Carlos and Queen Sofía of Spain, (pictured, below).

2002

2002

Wave, Santiago Calatrava’s kinetic outdoor sculpture, is dedicated, (pictured, left).

2006

• Meadows Foundation gives $25 million to Museum for acquisitions, exhibitions, education and director spending.

• Mark Roglán, (pictured, left), named director of the Meadows Museum.

• Mark Roglán, (pictured, left), named director of the Meadows Museum.

2007

Balenciaga and His Legacy, the first fashion exhibition developed and hosted by the Museum, opens at the Meadows Museum, (pictured, right).

2008

• Fernando Gallego and His Workshop opens at the Meadows after 5 years of study and research in collaboration with the Kimbell Art Museum and the University of Arizona Art Museum, (pictured, right).

• Meadows Museum exhibits From Manet to Miró: Modern Drawings from the Abelló Collection, the first partnership with Juan Abelló and Anna Gamazo.

2009

October 7 – Dedication of new sculpture plaza, which highlights the Museum’s newly acquired monumental sculpture, Sho by Jaume Plensa, (pictured, left).

2010

• September- Prado Partnership begins with loan of El Greco’s Pentecost, (pictured, right).

• The Museum acquires a full length portrait of King Charles II, by Juan Carreño de Miranda.

2011

• Start of the Meadows/Kress/Prado Fellowship.

• The Museum acquires Vicente López y Portaña’s portrait of the American, Richard Worsam Meade, the father of the Union General George Gordon Meade.

2013

• Sorolla and America opens at the Meadows Museum after 5 five years of research and study. Exhibition continues to The San Diego Museum of Art and Fundación MAPFRE (Madrid).

• Meadows Museum acquires a sixth Goya painting, Portrait of Mariano Goya, the Artist’s Grandson, 1827, (pictured, left).

• Meadows Museum acquires a sixth Goya painting, Portrait of Mariano Goya, the Artist’s Grandson, 1827, (pictured, left).

2014

Start of the Meadows/Mellon/Fellowship.

2015

The Museum celebrates its 50th anniversary with a historic commemoration ceremony, visits by former U.S. President George W. Bush and the Duke of Alba, and spectacular exhibitions of major private Spanish collections. The Meadows Foundation makes yet another historic gift to SMU of $45 million, $25 million of which is designated for the Museum.

2016

The Museum acquires its first painting by Salvador Dalí, L’homme poisson (1930).

Algur H. Meadows, 1899–1978

Born in 1899, Algur Hurtle Meadows grew up the third of seven children in Vidalia, Georgia. Meadows entered the oil business in 1921 as an accountant for Standard Oil Company in Shreveport, Louisiana. While at Standard, he obtained a law degree from Centenary College and in 1926 was admitted to the Louisiana State Bar. In 1928, he and a partner founded the General Finance Company, a syndicate of small-loan finance companies that became the General American Finance System in 1930. In 1936, he and two colleagues founded the General American Oil Company, and in 1937, General American moved its headquarters from Shreveport to Dallas. The company grew quickly in size and assets, due largely to an ingenious financing method developed by Meadows for acquiring oil-producing properties. By 1959, the company had acquired almost three thousand oil wells in fifteen states and Canada. Meadows believed that his life was greatly enriched by giving, and he demonstrated his commitment to philanthropic causes in 1948, when he and his first wife, Virginia, created The Meadows Foundation. Majority-governed by the Meadows family, the Foundation continues to advance Meadows’s legacy, and has disbursed over $1.1 billion in grants and direct charitable expenditures to over 3,500 Texas institutions and agencies..

Founding Director William B. Jordan, 1940-2018

The Meadows School of the Arts and Meadows Museum mourn the passing of William B. Jordan, founding director of the Meadows Museum in 1967 and a former chair of fine art at the Meadows School.

Remembering William Jordan at SMU

On July 1, 1967, William Jordan was named director of the Meadows Museum and chair of the division of fine art at what was then the School of the Arts at SMU. The announcement in The Dallas Morning News quoted then-dean Kermit Hunter as saying Jordan would “take charge of authenticating the more than 300 works of art donated by Dallas oil man Algur H. Meadows.” The desire for authentication came from Mr. Meadows on the heels of a forgery scandal that rocked the art world that year.

In a personal recollection about Algur Meadows written in the late 1990s titled “Algur Meadows: Un recuerdo personal” (Goya Revista de Arte, No. 273, 1999, pp. 343–52), Jordan recounted what happened.

“I first met Algur Meadows in 1967 when I was 26 years old, just finishing my doctorate in art history, and he was 67. I had the good fortune to work closely with him for the next 11 years on building the collection that today forms the major part of the Meadows Museum.”

Meadows had acquired a number of Spanish paintings in the late 1950s and had donated the collection to SMU in 1962, along with funds to construct the Meadows Museum. Unbeknownst to him, a number of the works were fakes. Then, in the mid-1960s, Meadows was swindled by two unscrupulous art dealers from Paris who sold him dozens of paintings for his personal collection, purportedly by major French artists such as Gauguin, Dufy, Chagall and Bonnard.

Having bought more than he had room for, Meadows approached a well-reputed local art dealer about selling some of them. “Only then, and in the follow-up investigation, did he discover that virtually all of them were fakes painted by the now infamous, but then unknown, Elmyr de Hory,” Jordan wrote. “This disclosure, which appeared in newspapers around the world in the spring and summer of 1967, was the biggest international art scandal of the 1960s, because Meadows was not the only victim of the scam, and it became the focus of Clifford Irving’s best-selling Fake.”

Jordan continued, “It was around this time, shortly after I had agreed to become the first director of the Meadows Museum, with [Meadows’] guarantee to begin the collection anew, and while Al Meadows was suffering a humiliation that would have driven a lesser man in the opposite direction of the art world, that I began to know him and to appreciate the measure of the man” (“Algur Meadows: Un recuerdo personal”).

According to Jordan, Meadows “resolved to rebuild the Meadows Museum and to rebuild his private collection. And he resolved to deal henceforward with only major galleries.” Jordan described this process:

As we began anew in 1967, the first step was to close the museum for several months over the summer, to begin the process of evaluating the existing collection. Even before the scandal about the French fakes in his home, Meadows had accepted that many of the Spanish paintings he had given to the university were unexhibitable and had asked that I determine which were worthy of retaining. The responsibility for doing that was too great to be borne alone by the inexperienced and very young man that I was then, so the task was shared with José López Rey, who had been my professor at New York University, and Diego Angulo Iñiguez, then director of the Prado Museum, both of whom were to remain close advisers and good friends of the museum over the years. Their evaluation became the basis for future decisions as to which paintings would be sold. In 1969 approximately 35 of the paintings were sold at auction in New York, realizing a total of only about $35,000. A few of the better ones were eventually traded to dealers as partial payment for new acquisitions. The remaining paintings that were not deemed exhibitable were retained for study purposes and for use in the teaching of connoisseurship, and these remain in the reserve collection today. (“Algur Meadows: Un recuerdo personal”)

Jordan said that for Algur Meadows, “a great part of the pleasure of collection was the deal he could make in acquiring a given picture, or a group of pictures, as the case might be.” Jordan wrote:

In the dizzy days of scandal in 1967, when I hardly knew him and had not yet bought a single thing for the collection, we visited the Wildenstein Gallery in New York, accompanied by López Rey. We were shown nine Spanish paintings that morning (including works by Zurbarán, Murillo and Goya), some of them extraordinary. After examining the paintings for a couple of hours, we adjourned for lunch. While walking to the restaurant, I told him I was sure we could choose several of them that would be a credit to the collection he wanted to rebuild. Whereupon he informed me that, in a private word with the gallery’s director, he had actually just bought them all. I was stunned, not just by his largesse, but mostly because I knew I did not want them all, and I thought the director was supposed to have some say in the matter. In the end, after a brief talk about the role of the director and about how we needed to deliberate over each acquisition, we did not buy them all, but we did buy most of them. He knew that if he bought more than one thing from a dealer, he could get them at a better price, and that mattered to him. In the end, no harm was done — far from it! — for among the paintings bought that morning was Goya’s recently rediscovered masterpiece Corral de locos (Yard with Madmen). Nothing so rash was ever done again, because Meadows quickly learned that the process of acquiring art for a museum is very different from doing so for oneself and that the role of patron has to be exercised in partnership with museum professionals. From that moment on, he was the exemplary partner. Rarely initiating any acquisition himself, he left the search to me, and gave me the necessary time to research and vet each potential purchase, while — especially at the first — reserving for himself the role of negotiator. (“Algur Meadows: Un recuerdo personal”)

Jordan said that Meadows “placed his trust in me, often buying the painting we decided to acquire without ever having seen it. On one important occasion that I recall, he stood behind me when no one else would do so. In 1976 I saw in Manuel González’s gallery in Madrid the awesome San Sebastián by Fernando Yáñez de la Almedina, which González had bought outside of Spain. Although no one knew it then, the painting had been acquired in the 1830s by King Louis Philippe of France and was displayed as a Yáñez in his Galerie Espagnole at the Louvre between 1838 and 1848. But the painting was unpublished and there was no record of it in the literary sources of Spanish art.” Experts he consulted told Jordan that “it was too good to be Spanish and must be Italian.” He said, “I could find no one willing to support the attribution to Yáñez. But, convinced in my own mind that it was by him, I urged Meadows to buy it despite the lack of consensus. He did, and for a considerable sum. … Today the Yáñez is universally regarded as one of the artist’s masterpieces and is among the most esteemed works in the Meadows collection” (“Algur Meadows: Un recuerdo personal”). The trust established between Jordan and Meadows was evident in a letter dated June 24, 1974, in which Jordan wrote to Meadows saying, “No benefactor that I can imagine would be as fine to work with. I consider this my life’s work and I consider myself very lucky.”

Jordan recalled the last acquisition for the museum purchased during Meadows’ lifetime:

Just a month before he was tragically killed in an automobile accident in 1978, at the age of nearly 79, I recommended to Meadows that we buy Velázquez’s Portrait of Queen Mariana from Edmond de Rothschild (through the intermediary of the London dealer Colnaghi). Although we already possessed two paintings by Velázquez, [Meadows] could not resist the freshness and immediacy of this sensitive portrait from life, which had been painted to record the change in the queen’s hairdo. Uncharacteristically, he asked for no concession in the price, only for two years to pay it out. He did not live to see the painting, which went directly from the seller to New York to be cleaned before coming to Dallas, but the obligation to buy it, of course, was honored after his death. The loss of Algur Meadows was an enormous blow to the city of Dallas.

Jordan remained at SMU for three more years after Meadows’ death, leaving in 1981 to become deputy director of the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth. The announcement at the time in The Dallas Morning News noted that, during his tenure at the Meadows, Jordan acquired about 75 works of art for the museum, including important paintings by Velázquez, Murillo, Ribera and Zurbarán. It also noted that he “purchased six important 18th– and 19th-century canvases by Goya and key 20th-century pictures by Picasso, Miro and Juan Gris.” In addition, he “built the Elizabeth Meadows Sculpture Garden collection, which includes works by Maillol, Lipchitz, Rodin, Henry Moore, David Smith and Claes Oldenburg.”

Jordan also served as chair of the Division of Fine Arts in the Meadows School from 1967 to 1973. He became a full professor at the Meadows School in 1975, teaching courses in the history of Spanish art as well as a course in connoisseurship, “Museums and Collecting.”

He remained a friend and advocate of the Meadows School and Meadows Museum in the ensuing decades. He was also a member of the Meadows School executive board, until resigning in early January 2018 due to illness. His involvement, vision and dedication to the field of Spanish art has left a lasting legacy. An internationally known scholar and authority on Golden Age Spanish art, he published major contributions to art history and curated important exhibitions on El Greco, Ribera and Juan van der Hamen, a still-life painter who was the subject of a major exhibition he curated at the Meadows Museum in 2006. His passing on January 22, 2018 is a sad loss for Dallas and all admirers of Spanish art.

Former Meadows Museum Director, John Lunsford, 1933-2019

Remembering John Lunsford (1933–2019), Former Meadows Museum Director and Art History Faculty Member at SMU, by Jennifer Smart (M.A. ’19)

When John Lunsford passed away earlier this year, remembrances of the man who touched a wide swath of the Dallas art world were shared across North Texas. As a curator at the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts (later the Dallas Museum of Art) from 1958 to 1986, he was an instrumental force in establishing the DMA as the world-class institution it is today. As director of the Meadows Museum from 1996 to 2001, he led the museum through an exciting period of change that culminated in the opening of its new, larger building on the SMU campus. Further, as adjunct associate professor in art history at the Meadows School of the Arts from 1968 to 1996, he taught more than a thousand students about a wide variety of non-Western art and connoisseurship. His former students and colleagues say his impact on them was memorable.

When John Lunsford passed away earlier this year, remembrances of the man who touched a wide swath of the Dallas art world were shared across North Texas. As a curator at the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts (later the Dallas Museum of Art) from 1958 to 1986, he was an instrumental force in establishing the DMA as the world-class institution it is today. As director of the Meadows Museum from 1996 to 2001, he led the museum through an exciting period of change that culminated in the opening of its new, larger building on the SMU campus. Further, as adjunct associate professor in art history at the Meadows School of the Arts from 1968 to 1996, he taught more than a thousand students about a wide variety of non-Western art and connoisseurship. His former students and colleagues say his impact on them was memorable.

“John was already an institution when I arrived at SMU in 1974,” said Dr. Alessandra Comini, professor emerita of art history. “His geniality and breadth of knowledge were delightful and his appetite for the new was ferocious.”

Lunsford is remembered as an enthusiastic, kind, and highly professional leader, but most of all for his commitment to simply engaging with the art, especially in an age when the museum world was becoming increasingly specialized and academic. “John was a true object lover who enjoyed looking at art and scrutinizing every detail,” said Mark Roglán, now the Linda P. and William A. Custard Director of the Meadows Museum, who joined the museum as interim curator just as Lunsford’s time as director was coming to an end. “It was always wonderful to hear him talk about art and listen to all the connections he could make across different cultures and styles. He was an astute connoisseur and walking cultural encyclopedia.”

Gregory Warden, SMU professor emeritus of art history and president of Franklin University Switzerland, took over as interim director of the Meadows Museum in 2001 when Lunsford stepped down. He also remembers Lunsford’s commitment to connoisseurship. “I had high regard for his curatorial eye,” he said. “And I appreciated his professionalism and calm demeanor in dealing with a wide variety of personalities.”

Michael Grauer, a curator, teacher, and expert on Texas art, was a student of Lunsford’s in the late 1980s. Although his teaching focused on non-Western art, Lunsford, a Dallas native, had an impressive depth of knowledge about historic Texas art and served as advisor for Grauer’s master’s thesis on the Texas painter Frank Reaugh. Grauer echoed the oft-repeated remembrance of Lunsford’s commitment to connoisseurship, and remembers Lunsford’s class on the subject as the best one he took when he was a student at SMU. “In the class, John tried to teach a bunch of budding art historians that art was more about looking and seeing than about documentation,” he said. “The lessons I learned were mainly that you could find all the documents in the world surrounding a work of art, but that doesn’t make it good or great. We had to learn to train our eyes to be discriminating and listen to our gut, our visceral response to a work of art.”

Bridget Marx, associate director and curator of exhibitions at the Meadows Museum, was a graduate student when she began working with Lunsford as a teaching assistant for Dr. Pamela Patton, the Meadows Museum’s curator during Lunsford’s tenure as director. “It was an exciting time to be a part of the Meadows Museum; not only was the new building being developed and constructed, the collection itself was being prepared for temporary exhibition in Spain,” she said. “John would joke that we were moving across the street, via Madrid.” She recalled Lunsford as a patient and generous leader who “never missed the opportunity to grow and encourage the love of museum work in a young student.”

His commitment to the mentorship of young students and professionals is echoed by another former pupil, Kathy Windrow, who earned three degrees at SMU under Lunsford’s tutelage and now teaches in the Meadows Division of Theatre and directs the SMU-in-Italy Arts and Culture program. She remembered Lunsford as regularly going out of his way to offer encouragement and support, sometimes even financial help, to students of all backgrounds. “Students followed him like groupies,” she recalled. “He was our guide through dangerous intellectual terrain, devoted to the work of teaching, his students, and above all to the works of art.”

“He was extremely confident, but never arrogant, about what he knew,” Grauer said. “He was always learning. His example to always seek to know and experience more is something I have never forgotten. He also ensured we knew that all art making is spiritual and that spirit inhabited and was inculcated—he would love that I used that word right there!— in all things.”

Lunsford’s legacy at SMU and especially at the Meadows Museum lives on. In addition to overseeing the Meadows permanent collection installment in its new home and the welcoming of the king and queen of Spain to the SMU campus for the building’s grand opening, he also secured the purchase of an El Greco canvas, Saint Francis Kneeling in Meditation, for the museum, and handled the commission of the monumental Santiago Calatrava sculpture, Wave, which today greets visitors at the entrance of the SMU campus.

Former Meadows Museum Director, Mark A. Roglán, 1971-2021

On October 5, 2021, the Meadows Museum, SMU, mourned the loss of its director, Dr. Mark A. Roglán (age 50), to cancer. The announcement came on the heels of his 20th anniversary with the institution, the leading center in the United States for exhibition, research and education in the arts and culture of Spain, which he had led as director since 2006.

On October 5, 2021, the Meadows Museum, SMU, mourned the loss of its director, Dr. Mark A. Roglán (age 50), to cancer. The announcement came on the heels of his 20th anniversary with the institution, the leading center in the United States for exhibition, research and education in the arts and culture of Spain, which he had led as director since 2006.

Under his leadership the museum tripled attendance; developed a major program of international exhibitions; created meaningful fellowships; produced insightful publications; constructed a new sculpture garden and outdoor spaces; made major acquisitions nearly doubling the collection; developed engaging and accessible educational programs; established strategic alliances with major museums worldwide; and raised millions of dollars in funding, most recently gifts totaling $6 million to establish a research institute.

A native of Madrid, Dr. Roglán joined the Meadows Museum as interim curator and adjunct assistant professor of art history in August 2001. He became curator of collections in January 2002 and senior curator in June 2004. Following a nationwide search, he was promoted to director in 2006, and after a $1 million dollar gift in 2013 establishing an endowment for the position, he became the Linda P. and William A. Custard Director of the Meadows Museum and Centennial Chair in the Meadows School of the Arts at SMU. On August 26 he presided over the founding of a new research institute within the museum, the Custard Institute for Spanish Art and Culture, established by gifts from the Custard family and The Meadows Foundation. The Custard’s gift named the director of the new institute in his honor.

Before coming to the Meadows Museum, Dr. Roglán worked as a curatorial fellow and a research associate in the 19th-century painting and sculpture department of the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid, Spain. Prior to his tenure at the Prado, Dr. Roglán served as a drawings department assistant with the Fogg Museum at Harvard University. Dr. Roglán received master’s degrees in both world history and art history and a doctorate in 19th- and 20th-century art from the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. In 2013 he obtained an MBA from the Cox School of Business at SMU.

Read a full account of Dr. Mark A. Roglán’s career

Watch a tribute to Dr. Mark Roglán – The Man and the Museum: Mark A. Roglán, 1971-2021

Architecture

The Meadows Museum is housed in a two-story collegiate Georgian red brick building of approximately 66,000 square feet that was designed by Chicago-based architects Hammond Beeby Rupert Ainge and opened in 2001. The first floor includes a museum shop, an education studio, a classroom, an auditorium, and several public areas suitable for receptions and other events. Underground parking provides all-weather access for museum visitors.

The Meadows Museum dedicated its plaza and sculpture garden, designed by Dallas-based Swiss architect Thomas Krähenbühl of TKTR architects, in October 2009. The museum entrance includes fountains and access stairs leading to the sculpture plaza from Bishop Boulevard. The plaza features a permanent installation of monumental modern and contemporary sculpture by major artists, including the centerpiece of the plaza, Sho (2007), a 13-foot-tall sculpture by contemporary Spanish artist Jaume Plensa. The plaza’s innovative design features four strategically located overlooks which provide shady, peaceful areas to view the sculptures. One of the overlooks provides a dramatic view of Santiago Calatrava’s moving sculpture Wave (2002), permanently installed below the plaza at street level.

The plaza and the Plensa sculpture acquisition were made possible through the support of patrons including Nancy Hamon and the late Jake Hamon, The Eugene McDermott Foundation, The Meadows Foundation, Richard and Gwen Irwin, The Pollock Foundation, the family of Mr. and Mrs. Richard R. Pollock and the family of Lawrence S. Pollock, III.

Prado at the Meadows

On September 12, 2010, officials from SMU, the Meadows Museum, and the Museo Nacional del Prado gathered at the Meadows to sign an agreement for the loan of three major paintings from the Prado over the course of three years and the exchange of curatorial fellows between the two institutions. The partnership was inaugurated on the same day with the opening at the Meadows of El Greco’s Pentecost in a New Context. Building upon the success of the first two years of this collaboration, on July 11, 2012, the Meadows and the Prado announced the expansion of their partnership with additional collaborative exhibitions. As Miguel Zugaza Miranda, director of the Prado at the time, remarked: “This agreement … realizes the vision of Al Meadows to start ‘a small Prado in Texas.’” Grants from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the Samuel H. Kress Foundation have provided additional support to the Meadows/Prado curatorial fellowships, which were concluded at the end of the 2017-2018 academic year.