Spanish Muse: A Contemporary Response

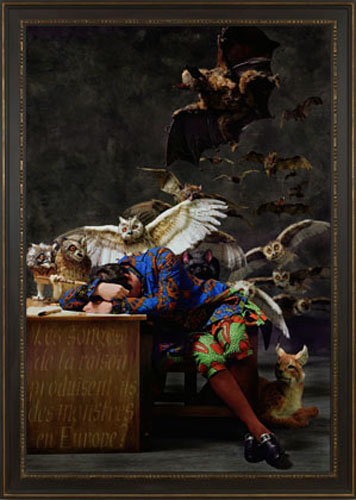

Image below: Yinka Shonibare, MBE (British-Nigerian, b.1962) The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (Europe), 2008 c-print mounted on aluminum. © Yinka Shonibare, MBE,, courtesy of James Cohan Gallery, New York

To commemorate the 45th anniversary of the Meadows Museum as a premier collection of Spanish art, this exhibition showcases contemporary works of art whose creators have been inspired by art produced—or collected—in Spain, and featured in some of that country’s great public collections. Created in a variety of media, including painting, photography, sculpture, video, and graphic art, these contemporary works will be installed alongside the permanent collection at the Meadows as a way to create meaningful dialogues and forge new connections between art of the past and present. The aim of this installation is to show how works of the past are major sources of inspiration for living artists from all over the world, including Africa, Europe and the Americas.

Featured in this exhibition are contemporary works of art from the last 10 years by José Manuel Ballester, Claudio Bravo, Jake and Dinos Chapman, John Currin, Yinka Shonibare, MBE, Thomas Struth, Eve Sussman | Rufus Corporation, and Manolo Valdés.

Velázquez’s iconic Las Meninas is the point of departure for the works of both Eve Sussman | Rufus Corporation and Manolo Valdés. The snapshot-like, proto-photographic quality of Las Meninas and the psychological charge of the scene prompted Sussman to create the installation 89 seconds at Alcázar (2004). The set design and costumes of the piece were created faithfully to the time period, while the choreography by Rufus collaborator Claudia de Serpa Soares provided the opportunity to imagine Velázquez’s scene through gesture. The performance that unfolds on screen explores the narrative intrigue of the painting and further implies psychological nuance.

Performance is the operative word: 89 seconds at Alcázar was shot as a single, uncut choreographic work. With minimal edits that escape perception, the fluid motion of the 10-minute piece is built of moments that come together and then fall apart again.

Manolo Valdés, a Valencian artist, also quotes from the iconic and emblematic fashion in the Court of Philip IV of Spain, using its image of Queen Mariana for his sculpture. Her schematic and unique image has become synonymous with Spain’s artistic identity, a major source of inspiration for Valdés throughout his career.

Claudio Bravo and John Currin have both become experts in the painting techniques of the Old Masters. A Chilean artist who resides in Morocco, Bravo has the extraordinary ability to breathe life into otherwise mundane objects through verisimilitude. His two paintings featured in the Meadows exhibition, Pumpkins (2005) and Beige Paper (2007), call to mind Zurbarán’s magnificent light effects. Currin’s supreme technical skills merge with subversive subject matter in his canvases. Common sources of inspiration for Currin are the European Old Masters, magazine advertisements from the 1950s, and politics. Currin’s trajectory over the past two decades has taken him from abstraction to increasingly refined figuration. The iconography of Currin’s figurative work runs the gamut from bawdy women to quirky riffs on Old Master themes. Rippowam (2006) combines the ribaldry of a 17th-century bacchanal à la Velázquez with a palette of Goyaesque yellows and blues, and transports the scene forward to a happy rendezvous seemingly from just a few decades ago.

In José Manuel Ballester’s El Jardín Deshabitado (2008), the artist has removed all human references from Bosch’s famous triptych of 1500-05, The Garden of Earthly Delights. The formerly subordinated landscape of Bosch’s moralizing allegory has been transformed into the focus of Ballester’s work through digital technology. Despite his subtractive technique, Ballester’s recreation does not interfere with Bosch’s intent or purpose. Ballester’s garden, much like Bosch’s, is an object of contemplation. In Ballester’s case, however, there are no distractions or temporal references to obstruct the meditative view.

The choice of Bosch as a source for Ballester is also significant as it pertains to the idea of the Spanish muse. Bosch’s bizarre paintings were well loved by Philip II. The Garden of Earthly Delights was purchased at auction in 1593 and installed at the Escorial, (Royal Palace), where it remained until 1939. Now at the Prado Museum, Bosch’s triptych, as well as many other masterpieces from other non-Spanish schools, is emblematic of the foreign artist as an instrument in forging the Spanish school of painting.

Thomas Struth’s Museo del Prado 8-1- 8-5 photographs (2005) are part of the German artist’s series of work dedicated to museums’ interior spaces, paintings and viewers. The five photographs of this suite were shot in the Prado gallery where Las Meninas and other Velázquez portraits of the Hapsburg royals are installed. Struth’s photographs document flocks of visitors in the popular gallery. As part of the Meadows exhibition, Struth’s works are at the core of the concept of muse. Etymologically, “museum” derives from the Greek mouseion, “seat of the Muses.”

A criticism of art museums has been that, as repositories of works from diverse periods, they destroy the original contexts of the works of art. Struth’s museum photographs offer a metahistorical approach to this problem, wherein the work of art itself—in this case the photographs—has been created in a museum. Directing our attention to the photographs, we as viewers observe viewers who view—or in some cases idle in front of—the paintings. Past has been connected with present, which in turn will connect future viewers of Struth’s works.

For Yinka Shonibare, MBE (Member of the Order of the British Empire), deconstructing ideas of empire is a central theme. The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (Europe), dated 2008, is one of a group of five large photographs which quotes Goya’s iconic series Los Caprichos. Each photograph of the suite represents one of five continents (Europe, Africa, America, Asia and Australia). The nationality of the sleeping man in each photograph is “mismatched” with his respective continent. The Dutch batik fabric worn by the sleeping figure—designed in Indonesia (former Dutch colony), manufactured in England, and exported to Africa—is also a questioning of identity as defined by empire. Shonibare’s response to Goya is well attuned to the Spanish artist’s critique of Enlightenment ideals. In each photograph, Shonibare inverts Goya’s pronouncement that “El sueño de la razón produce monstruos” (“The sleep of reason produces monsters”) into a question. He asks in French whether such dreams produce monsters in each of the continents. For the first time since its creation, Shonibare’s photograph will be exhibited at the Meadows Museum alongside the Goya print which inspired it.

When it comes to reworking Goya, there exists no more notorious a pair than Jake and Dinos Chapman. The British brother-artists incited an outcry when they literally reworked an entire late series of Goya’s Disasters of War and Los Caprichos printed in 1937 from the original plates. Penciled into Goya’s prints are cartoonish characters, monsters and clowns’ heads. Critics have described the artists’ work on Goya in both positive and negative terms as vandalism; the artists would insist that they are “rectifying” Goya. In defense of their actions, the Chapman brothers cite the example of Robert Rauschenberg, who erased a drawing by Willem de Kooning, which the older artist had given to him. Rauschenberg said he had done this out of admiration for de Kooning. Whether it is defiant love or defacement in the case of Jake and Dinos Chapman versus Goya, their obsession is a clear indicator of the Spanish master’s perpetual influence.

Ten prints from the 2005 series, Like a dog returns to its vomit (from Goya’s Los Caprichos), will be shown at the Meadows. This is the first time any of Jake and Dinos Chapman’s “reworked and improved” Goya etchings will be exhibited at a U.S. museum.

Spanish art from diverse periods continues to inspire artists on a global level. This exhibition, which intersperses contemporary art with the entire Meadows permanent collection, is the first of its kind at our museum.

This exhibition has been organized by the Meadows Museum and funded by a generous gift from The Meadows Foundation.

Carrie Sanger

Marketing & PR Manager

csanger@smu.edu

214.768.1584