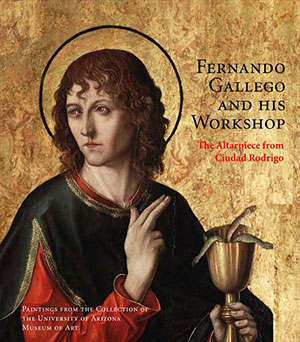

Fernando Gallego and His Workshop: The Altarpiece from Ciudad Rodrigo

Paintings from the Collection of the University of Arizona Museum of Art

The monumental altarpiece from the cathedral of Ciudad Rodrigo by Fernando Gallego and Maestro Bartolomé is among the greatest artistic treasures created in medieval Iberia. Painted between 1480 and 1500 in the Castilian province of Salamanca, its 26 panels visualize Christian history from Creation to the Last Judgment. The work is now part of the Samuel H. Kress Collection at the University of Arizona Museum of Art in Tucson. Since 2003, when the Meadows Museum initiated the altarpiece study, At the Meadows (Spring 2006 and Fall 2007) has kept our members abreast of the progress of this unprecedented undertaking, which involved close collaboration among scholars at the Kimbell Art Museum, the Getty Research Institute, and Madrid’s Prado Museum. Last year the technical and art historical research concluded. This spring the Meadows Museum celebrates the project’s culmination with a unique exhibition that features not only the paintings, but also the study.

All 26 altarpiece panels are displayed on a curved wall in the central of the Jake and Nancy Hamon spaces. To emphasize the new scholarship, much of which was aimed at gaining insight into Gallego’s and Bartolomé’s workshop practices as well as identifying which artist completed each panel, the paintings are organized by artist rather than narrative subject matter. To the left side of the entrance, Gallego’s works appear; to the right are Maestro Bartolomé’s pieces. Presiding over the space, in the center of the wall, is Bartolomé’s Chaos, flanked by The Temptation and The Creation of Eve. Although the altarpiece’s inscription dates it to 1480-88, these three panels are the only ones that were added later, after 1493; their apocalyptic iconography is derived from a book called the Nuremberg Chronicle, which was printed that year in Germany. The paintings attributed to Fernando Gallego and his workshop, complete the altarpiece’s narrative panels and highlight the individualized style and technique of the artists in Gallego’s workshop who nevertheless worked in union to create a single, harmonious work of art.

The three paintings from the predella (bottom row of the altarpiece) are the most accomplished, lavishly gilded, and representative of Gallego’s artistic gifts. They are installed individually on specially-built pedestals. Their exceptional quality results from their original location in the bottom of the altarpiece because they are closest to eye level and to the altar. Each painting depicts two apostles. Although only three panels survive, a total of six – to accommodate all 12 of Christ’s disciples – seem certain to have existed in the original altarpiece. Each saint’s animated, individualized personality represents Fernando Gallego at his absolute best; these works are featured prominently in the center of the gallery. Wall text guides viewers through the display and introduces them to the artistic personalities who created the vibrant altarpiece.

Complementing the central gallery paintings, all remaining spaces are devoted to the altarpiece’s technical analysis. Fifteen full-sized infrared reflectogram mosaics (eight by Gallego, seven by Bartolomé) are installed on light boxes, illuminating the artists’ underdrawings for the first time. Here the method used to reveal the preparatory sketches and an analysis of each painter’s drawing technique are explained in illustrated text panels. Other galleries highlight the often significant compositional changes made between underdrawings and paintings, as artists developed their images, along with issues of style and attribution. The Kimbell Art Museum’s conservation studio, where the technical analysis was conducted, is explored using photographs of the scientific equipment and other tools utilized in the study to acquaint viewers with the technology of art conservation.

By exploring the altarpiece creators’ artistic personalities using the latest technology and fresh art historical research, this exhibition offers a more comprehensive look at the Ciudad Rodrigo altarpiece than ever – opening new perspectives on Gothic painting in Spain – and inspires a revived appreciation for the individual talents involved in its production. This exhibition and study has been organized by the Meadows Museum, SMU in association with the University of Arizona Museum of Art, Tucson. A generous gift from The Meadows Foundation has made this exhibition and study possible, with additional support from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation.

Conservation

Beneath the Surface of a Late 15th-Century Spanish Treasure: The Altarpiece from Ciudad Rodrigo by Fernando Gallego and His Workshop

In September 2006, the Kimbell Art Museum’s paintings conservation department began the first technical study of Fernando Gallego’s Ciudad Rodrigo altarpiece, one of the most significant Spanish works of this kind created in the late 15th century. The Kimbell study endeavored to learn more about the workshop practices of Fernando Gallego, the famous painter from Salamanca, as well as those of his collaborator, Maestro Bartolomé. In late 15th-century Castile, master painters often worked together to produce major altarpieces. Even before the Kimbell study, differences in style and technique among the 26 existing panels had suggested to scholars that two independent workshops joined forces to take on the enormous Ciudad Rodrigo commission.

According to an early inscription on the framework, the altarpiece traditionally was dated to between 1480 and 1488. We now know that at least three panels were added several years later, because their imagery is based on woodcut illustrations from a book known as the Nuremberg Chronicle, which was published in Germany in 1493.

The technical study of the Ciudad Rodrigo panels—like the altarpiece’s creation—was an ambitious project that required several colleagues’ collaboration. At the Kimbell, Chief Conservator Claire Barry and her assistant Elise Effmann worked on all aspects of the examination, which included X-radiography and infrared reflectography. Inge Fiedler, conservation microscopist from the Art Institute of Chicago, conducted pigment analysis, using polarizing light microscopy, on a number of panels attributed to both artists. Fiedler took several pigment samples from areas with color notes in panels attributed to Fernando Gallego and his workshop. Michael Schilling and Joy Mazurek, conservators at the Getty Conservation Institute, conducted medium analysis on a selection of samples, using gas chromatography/mass spectroscopy. Peter Klein, dendochronologist (one who studies tree rings) from the University of Hamburg in Germany, identified the wood and joining methods used to construct the large panels.

Recent technological advances in infrared reflectography facilitated capture of images of preparatory underdrawings, an essential aspect of the artists’ techniques. InfraCAM SWIR, manufactured by FLIR Systems, was used in this study. Since only small areas could be examined at a time, hundreds of exposures from each panel were taken to create infrared reflectogram mosaics of each painting’s full composition. The individual exposures were then digitized and assembled on a computer using Adobe Photoshop software, eventually creating a complete record of these previously undocumented preliminary sketches.

The personal character of each artist’s underdrawing effectively distinguished Fernando Gallego’s work from that of Maestro Bartolomé; clear stylistic differences and working practices became apparent. Fernando Gallego, for example, made frequent color notations in drapery areas; no such inscriptions were found in the panels attributed to Maestro Bartolomé. The infrared examination also revealed that Bartolomé relied more heavily on prints and tracings, and made significant changes to his compositions as he developed his images.

Much of Fernando Gallego and His Workshop: The Altarpiece from Ciudad Rodrigo—Paintings from the Collection of the University of Arizona Museum of Art highlights the technical analysis of the altarpiece, including installation of the life-sized infrared reflectogram mosaics of 13 of the panels. Displayed on a light box, each underdrawing—never meant for the public eye—is visible for the first time in 500 years. Other galleries in this exhibition are devoted to the styles and techniques of the artists involved in the altarpiece’s creation, as well as the creative changes each painter made between the drawing and painting phases of their works. Another gallery, devoted to the Kimbell conservation studio, identifies the technologically advanced equipment that made these discoveries possible. An essay that Barry authored, summarizing the technical study results, is included in the scholarly catalogue that accompanies the exhibition.

Carrie Sanger

Marketing & PR Manager

csanger@smu.edu

214.768.1584