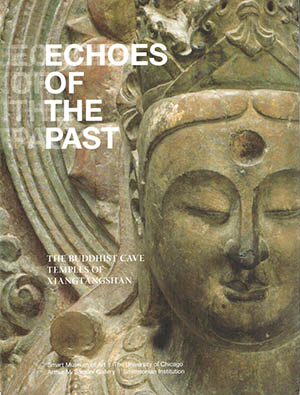

Echoes of the Past: The Buddhist Cave Temples of Xiangtangshan

This exhibition represents the culmination of a six-year project that began in 2004 at the Center for the Art of East Asia at the University of Chicago. The project’s aim was to research and “reconstruct” Xiangtangshan, a series of six-century Buddhist cave temples hollowed out from the living rock in a mountainous region in northeast China. Although they survive to the present day, the temple interiors were severely damaged in the early twentieth century when large numbers of stone figures and fragments were removed and offered for sale on the international art market. Using advanced technology in conjunction with straightforward research, the team studied the history of these grotto temples and investigated their subsequent despoliation in an effort to reconstruct the original appearance of the caves’ interiors. A focal point of the exhibition is the digital recreation of one of the largest cave temples of Xiangtangshan, by which visitors can better understand the architectural setting in its original context. The results of these efforts form the basis of this exhibition.

Xiangtangshan, or the “Mountain of Echoing Halls,” is a Buddhist devotional site created during the brief Northern Qi dynasty (550-577). Carved into the mountains in the southern Hebei province of Northeastern China, Xiangtangshan originally comprised a total of eleven man-made caves divided between two main locations, Bei Xiangtangshan and Nan Xiangtangshan.

Bei Xiangtangshan (the northern group of caves) is both the earliest and most ambitious of the complex. Associated with the reign of Wenxuan (r. 550-559), the first emperor of the Northern Qi dynasty, Bei Xiangtangshan is comprised of three caves: North, Middle, and South. The North Cave, also known as “The Great Buddha Cave,” is the largest of all eleven caves, measuring approximately 40 feet in height with an imposing interior area of over 1600square feet. Nan Xiangtangshan (the southern group) is located approximately nine miles from the northern group. Smaller in scale, these seven caves are arranged in two levels. While the floor plans of these southern caves are similar to those of their counterparts in the north, their reduced size suggests that they were not commissioned by imperial patrons. Echoes of the Past: The Buddhist Cave Temples of Xiangtangshan focuses only on these two groups, northern and southern, the sources for all of the sculpture in the exhibition.

In their original state, the limestone caves were filled with an impressive array of images—some carved out of the living rock itself and others from quarried stone that were then set into place. Many of these statues were figures of either large-scale Buddhas or their surrounding attendants including monk disciples, and enlightened spiritual beings called bodhisattvas and pratyekabuddhas. Additional figures lined the walls surrounding the various altars, along with relief carvings of lotus blossoms, flaming jewels, and winged monsters. Incised texts of passages from the Avatamsaka Sūtra, and other scriptures such as the Mahaparinirvāṇa and Queen Śrīmālā Sūtras, were carved into cave walls, spelling out the Buddha’s revelations about nonattachment and other concepts to be mastered on the path toward enlightenment. In their entirety, these caves housed an awe-inspiring world below ground, and the concentrated gathering of Buddhist-inspired images is a clear indication of their purpose: the promotion of the Buddhist faith, which had been deemed the favored religion at the start of the Northern Qi dynasty.

The Northern Qi period, which lasted for only a brief twenty-eight years, was divided into six reigns. Three emperors of the short-lived dynasty exerted particular influence over the period’s religious affinities and artistic production. These emperors were the first, fourth and fifth of the dynasty: Wenxuan (550-559), Wucheng (561-565), and Houzhu (565-577). Wenxuan, above all others, is primarily remembered for his lavish temple building campaigns, and it was he who in 555 intervened in the competition between Buddhism and Daoism by suppressing Daoism. Stating limited government resources as the underlying motivation for his proposition to have just one religion receiving state patronage, Wenxuan organized a debate in which the superiority of each religion was to be argued. Buddhism prevailed, thus initiating an era of temple and pagoda building that was meant to glorify the empire while inspiring Buddhist devotion. This in turn set the standard for his descendants, their courtiers, and the artisans they commissioned.

It was in this manner that the Northern Qi period laid the foundations for artistic production. During a period of great artistic experimentation, one important characteristic emerged: figures gained a sense of physicality and became more three-dimensional, as opposed to earlier sculpture that was much flatter and marked by elaborate linear surface patterns meant to indicate garment folds. This new type of figural sculpture dominated the decorative program of the Xiangtangshan grottoes. As a result of this distinctive artistic progression, the beauty of these sculptures attracted the attention of modern private collectors and museums alike, all of whom were eager to own an example of this newly “re-discovered” art. Accordingly, the cave temples suffered extensive losses of their carvings during the lengthy period of despoliation that began around 1910. While anything and everything became a target within the caves, if an entire figure could not be easily removed, the heads and hands of the statues were among the principal elements chiseled off and sold by dealers outside China.

A selection of noteworthy sculptures from both the northern and southern cave groups has been brought together for the current exhibition from museum collections in the United States and Europe for the first time since they were taken from the caves a century ago. The viewing experience and understanding of these religious images is enhanced by accompanying digital installations, which include a “pilgrimage video,” touch screen monitors and a three-dimensional “digital cave.” The digital cave, which represents the South Cave of the northern group, was created by the media artist Jason Salavon and serves as a grounding centerpiece for the rest of the exhibition. Three rear projection screens—arranged in an open-sided square to evoke the configuration and size of the original cave hall itself—present in a looped sequence an evocative montage of moving and still images of the cave’s three altars, depicted in both broad panoramas and in close-up detail. Black-and-white photographs of the cave taken in the 1920s document the site after the first removal of sculptures had already taken place, while three-dimensional digital images in high-resolution color record the temple interior as it exists today. Through a dramatic superimposition of three-dimensional digital scans of sculptural fragments removed from the altars in the first decades of the last century, the South Cave’s modern history is shown in different states of damage, preservation and virtual reconstruction.

In order to compile these accurate and sophisticated representations, a host of technology was employed by Katherine R. Tsiang, guest curator and Associate Director of University of Chicago’s Center for the Art of East Asia, Lec Maj, the project’s technical director, and a dedicated team of researchers. The cave itself, as well as approximately 100 objects believed to have been created for Xiangtangshan and now held in various institutions and private collections worldwide, were thoroughly scanned and photographed. To create the highly detailed three-dimensional images, each object was captured with literally hundreds of overlapping scans that were later pieced together to form a unified and representative three-dimensional image of the object. The 3D scans provided the researchers with remarkable detail, including size, surface contours, chisel marks and evidence of damage, all of which have proven helpful in the project team’s mission to accurately match dispersed fragments to their original location.

The Seated Buddha is just one of the sixteen sculptures on display, and is a perfect example of how the research team’s thorough work has significantly advanced a more comprehensive understanding of Xiangtangshan. Previously dated to the twelfth century, this seated Buddha statue was recently reassigned to the Northern Qi period due to similarities found in the concentric designs of the halo of the Buddha with the carved haloes of the colossal Buddhas located in the North cave of the Northern group.

The works on view are on loan from the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, the San Diego Museum of Art, the Victoria and Albert Museum, and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

Echoes of the Past: The Buddhist Cave Temples of Xiangtangshan is organized by the Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago and the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Major funding is provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Leon Levy Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation and the E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Foundation. The catalogue was made possible by Fred Eychaner and Tommy Yang Guo, with additional support from Furthermore: a program of the J.M. Kaplan Fund.

Additional support for the Meadows Museum’s presentation is generously provided by The Meadows Foundation.

The exhibition is supported by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this exhibition do not necessarily reflect those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Promoting the Protection of Chinese Cultural Heritage

When were the sculptures removed from Xiangtangshan?

The objects shown in this exhibition were taken from Xiangtangshan between 1910 and about 1930. The majority passed through the hands of the Chinese art dealer C. T. Loo, who had commercial operations in Beijing, Shanghai, Paris, and New York. Other dealers handling these sculptures included Edgar Worch, based in Paris, and Yamanaka & Company, located in Kyoto and New York.

Museums in the United States, Europe, and elsewhere purchased these objects or received them as gifts between 1913 and 1952, many decades before international laws were enacted to promote the protection of cultural patrimony. The museums have conserved and shared the objects with the public for more than half a century.

What policies and regulations are now in place to protect sites like Xiangtangshan?

In 1970, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) passed the first international convention to protect cultural property and prohibit its illicit sale. Along with many other countries, China, the United States, and the United Kingdom ratified this agreement, which forbids the acquisition or display of works illegally removed from their nation of origin after 1970.

What work is underway to preserve Xiangtangshan?

While they are still active sites of Buddhist worship, the Xiangtangshan caves are governed by the Fengfeng Mining District Office for Protection and Management of Cultural Properties. This supervisory government agency—responsible for protecting, documenting, and restoring the caves—actively contributed to this exhibition.

Carrie Sanger

Marketing & PR Manager

csanger@smu.edu

214.768.1584