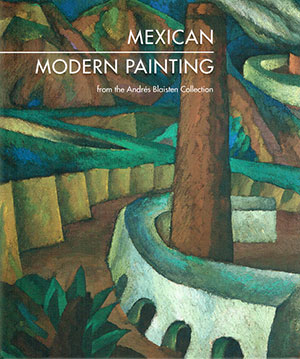

Modern Mexican Painting: From the Andrés Blaisten Collection

This summer, visitors to the Meadows Museum will have the opportunity to experience one of the greatest collections of modern Mexican art in the world. Modern Mexican Painting from the Andrés Blaisten Collection will feature a selection of eighty paintings from this singular group of works.

Andrés Blaisten, whose collection is comprised of over 8,000 works of art—including paintings, sculpture, drawings, and prints—first began collecting while studying painting at the Academy of San Carlos in Mexico City in the late 1960s. At first casually buying paintings from his academy friends, Blaisten soon dropped out of the academy and alongside his business ventures, devoted himself to selecting art that reflected his own relationship with Mexico. Although Blaisten has acquired works from various periods, this exhibition focuses on a predominant interest of his: paintings created in Mexico in the first half of the twentieth century.

By virtue of their diversity, the paintings chosen for the exhibition demonstrate the social, political, and artistic patchwork that shaped Mexico and by extension, its art, from the beginning of the twentieth century until midcentury, when the artists fell into the shadow of the Cold War and their individual voices were swallowed into the machine of Communism.

Mexican Modernism was a polyphony of artistic voices, each expressing a particular point of view. This exhibition disproves the traditionally held idea that Mexican art of the early twentieth century was insular, its artists working for the most part without an awareness of avant-garde European art. In addition to the giants such as Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros, all represented in the exhibition, other Mexican artists visited Europe, while many others were aware of the theories and formal elements that informed the various“-isms” taking place on the other side of the Atlantic. At the same time, the Mexican Moderns also took great pride in their indigenous Mexican history, honoring the astonishing achievements and folkloric creation myths of the Aztec Empire and other contingents of pre-Hispanic Mexico. The fascinating juxtaposition of the Old and New World within the context of Mexican Modernism is evident in the display of the Museo Colección Blaisten at the Centro Cultural Universitario Tlatelolco (CCUT), an institution under the auspices of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). The Museo Colección Blaisten, a permanent installation of a portion of the collection at the CCUT, overlooks the archaeological site of Tlatelolco, the sister city of Tenochtitlan. A mural by Siqueiros also happens to be within walking distance from this cultural center.

Traditionally, 1921, the year of the first post-revolutionary murals under José Vasconcelos, newly appointed Minister of Public Education, has been considered the benchmark for the genesis of modern Mexican art. However, recent scholarship has shown that the artistic revolution began even earlier in the twentieth century. As early as 1909, Vasconcelos spearheaded a group known as the Athenaeum of Youth which challenged the Eurocentric bias of Mexican determinist politics. Examples of art from these early decades demonstrate that Mexican artists could glean from European art while simultaneously embracing their own identity. In the exhibition are works by Germán Gedovius, who studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, and a few of his pupils, including Saturnino Herrán. The ennui of Symbolism and other fin de siècle art movements encountered by Gedovius was adapted by Herrán, who conceived his own symbols of Mexican national identity in his art.

Students protesting artistic academicism helped to fuel the development of the Open-Air Painting School, established between 1913 and 1914. Flourishing in the 1920s, the Open-Air Painting School produced a number of artists represented in this exhibition, including Francisco Díaz de León, Gabriel Fernández Ledesma, Fernando Leal, Fernando Castillo, and Rosario Cabrera, along with several others. Alfredo Ramos Martínez, also represented in the exhibition, established the open-air model, based on the nineteenth-century Barbizon school in France. In this new model, the people, architecture, and landscape of rural Mexico replaced reproductions of Classical and Renaissance art as the focus.

A group of artists who challenged the heavy-handed politicized art of the 1920s and 1930s was the Contemporáneos. These artists focused on formal elements of composition rather than the idyll of rural Mexico and related historical or indigenous themes. Associated with the titular journal of literature and art, those counted among the Contemporáneos included Manuel Rodríguez Lozano, Julio Castellanos, Agustín Lazo, Rufino Tamayo, María Izquierdo, and Juan Soriano. The composition of a work, rather than subject matter, was their primary focus. Several of the Contemporáneos incorporated Surrealist elements in their canvases. While these painters did not wholly ascribe to Surrealist theory, their works garnered the attention of André Breton, who organized the Exposición Internacional del Surrealismo in the Galería del Arte Mexicano in 1940. Author of the first Surrealist manifesto, Breton called Mexico the “most surrealist country in the world” after a visit in 1938.

A major theme that connects the works of the exhibition is that of mexicanidad—literally translated as Mexicanness. In speaking about María Izquierdo, who is represented by two paintings in the exhibition, Blaisten could have also been speaking about the phenomenon of Mexican Modernism as a whole: “In her painting María Izquierdo does not ask what Mexicanness is … she exhibits and refines … being Mexican.” In other words, the concept of mexicanidad became, in the grand sum of the works of the Mexican Moderns, not a question, but an assertion. Expressing one’s identity—as a Mexican and as an artist—could take the form of an introspective self-portrait or a sophisticated likeness of an upper-class individual; a provincial landscape or a rendering of an industrial utopia. The Mexican Modern could delve at various depths into the theories and formal elements of the movements of the European avant-garde, or alternatively, re-create in their painted images a Mexico yet untouched by Spanish explorers.

Political pressures at midcentury ultimately stifled the momentum of the Mexican Moderns. Realism, overarching many of the creative manifestations of these artists, became a tool for political propaganda. Leon Trotsky and Joseph Stalin not so indirectly forced the hand of these artists, who lost their autonomy to the vicissitudes of authoritarian power.

This exhibition is organized by Museo Colección Blaisten of the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico in cooperation with the Phoenix Art Museum, The San Diego Museum of Art, and The Meadows Museum at Southern Methodist University.

Carrie Sanger

Marketing & PR Manager

csanger@smu.edu

214.768.1584